Do I have joint hypermobility?

Joint hypermobility, sometimes described as being ‘double-jointed’, is when a person has a greater than normal range of movement in one or more joints. A person is born with differences in their connective tissue, where the collagen is more flexible and allows pain-free movement beyond the range of most people’s joints.

Joint hypermobility, sometimes described as being ‘double-jointed’, is when a person has a greater than normal range of movement in one or more joints. A person is born with differences in their connective tissue, where the collagen is more flexible and allows pain-free movement beyond the range of most people’s joints.

Joint hypermobility is relatively common, with around 20–30% of the population having some degree of hypermobility, either in isolated joints or throughout the body. It is more prevalent in younger people, females and certain ethnic groups. The condition exists on a spectrum. Some people have joint hypermobility without it causing any problems and in activities such as gymnastics or dance, where high levels of mobility are required, it can even be an advantage.

At the other end of the spectrum, some people experience ongoing pain, recurrent injury or difficulty controlling their joints. This can be the case in connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Hypermobility can also develop in response to repetitive strain or trauma and is commonly seen in sports involving repeated movement patterns.

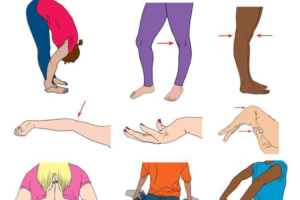

Joint hypermobility is often assessed using the Beighton score, which gives an indication of generalised hypermobility but does not capture everyone with symptoms. In people with more widespread hypermobility, joints such as the knees, elbows or thumbs may move beyond the usual range and some people can bend forward and place their hands flat on the floor with straight legs. Others may have only one or two hypermobile joints with no obvious outward signs.

Because of the increased joint movement, the brain can misjudge where a joint is in space, which may contribute to clumsiness or poor coordination. Muscles around hypermobile joints often work harder to provide stability, leading to tension, fatigue and a feeling of stiffness rather than looseness.

Features of joint hypermobility syndrome

- Pain is often the overriding symptom

- Increased susceptibility to injury due to connective tissue fragility

- Slower healing times and prolonged rehabilitation

- Higher prevalence of fibromyalgia and persistent pain conditions

- Reduced joint proprioception (awareness of joint position)

- Associations with anxiety, panic symptoms and autonomic nervous system issues such as palpitations, dizziness or fainting

Treatment and advice

Treatment focuses on improving balance, proprioception, joint control and strength through the available range of movement. Activities such as Pilates and swimming can be particularly helpful, as they encourage whole-body muscle engagement to support joints rather than isolating individual movements.

People with hypermobility are generally advised not to push into their end-range flexibility when exercising. Static stretching and movements that stress joints beyond their controlled range are often unhelpful. Using mirrors or visual feedback during exercise can assist with movement awareness and control.

Osteopathic treatment can help people with hypermobility by reducing muscle overactivity, supporting joint control and improving confidence in movement.

Appointments can be booked via my online diary.